Parental consent laws vary by state by the type of health care service. This piece brings you an overview of the issue and lists several studies and resources to help you with your reporting.

by Naseem S. Miller | November 29, 2021 | coronavirus, law, Vaccines

You are free to republish this piece both online and in print, and we encourage you to do so with the embed code provided below. We only ask that you follow a few basic guidelines.

by Naseem S. Miller, The Journalist's Resource

November 29, 2021

This piece is regularly updated with new research about parental consent for the COVID-19 vaccine. It was last updated on April 6, 2022.

Since the U.S. Food and Drug Administration granted emergency use authorizations for a COVID-19 vaccine for children this year, polls have shown that a portion of parents are hesitant about vaccinating their children, even though studies have shown that the vaccines are safe and effective.

In the October Kaiser Family Foundation COVID-19 Vaccine Monitor’s report, half the parents said their teens had gotten the vaccine or will do so right away, and 27% of the parents said that they would vaccinate their 5-to-11-year-olds right away as soon as it becomes available in November. But 30% of parents said they won’t get the COVID-19 vaccine for their 12-to-17-year-olds or 5-to-11-year-olds.

Not all adolescents agree with their hesitant parents and, as news reports have documented in recent months, some are trying to get their COVID shots against their parents’ wishes.

Even before the coronavirus pandemic, some teens fought for the right to get their shots without their parents’ consent. In 2019, an Ohio high school senior Ethan Lindenberger testified in a congressional hearing about how he couldn’t get his recommended childhood vaccines because his mother was an anti-vaccine advocate. He got his immunizations as soon as he turned 18 and, now at 20, he’s an advocate for youth who want to get their COVID vaccine against their parents’ wishes.

This disagreement has once again brought to the forefront a question: Do kids, particularly adolescents, need their parents’ consent to get the COVID-19 vaccine?

There’s no simple answer to the question and in recent months medical, legal and ethical experts have weighed in on the issue, as you’ll learn in this research roundup.

Parental consent laws vary by state and by the type of health care services, such as screenings or vaccinations. Some states allow minors to obtain contraceptive, prenatal and sexually transmitted illness services without parental involvement. Connecticut, Maine and the District of Columbia have laws allowing minors to consent to abortion services, while Alaska, California, Montana, Nevada, New Jersey and New Mexico have parental consent laws that are permanently or temporarily not in effect. A few states, including Alabama, Alaska, California, Delaware, Idaho, New York, Oregon, and South Carolina, plus Washington, D.C., allow adolescents to get the HPV vaccine without parental consent.

Meanwhile, only a few states, including Washington, abide by “mature minor doctrines,” which allow minors deemed “mature enough” to understand the risks, benefits, and implications of their decisions to receive any care “within the mainstream of medical practice, not high risk, and provided in a non-negligent manner” without explicit parental approval, explain Nina Shevzov-Zebrun and Dr. Arthur Caplan in a recent paper.

Two guiding principles overlap with the state laws, Shevzov-Zebrun and Caplan write. First, all states have statutes that permit minors who are married, emancipated, pregnant or in the military to be in control of their personal health decisions. Second, “minors may typically seek and consent for services related to sexually-transmitted infections, pregnancy, family planning, and substance-related concerns without consent from parents, although specific laws vary by state,” the authors write.

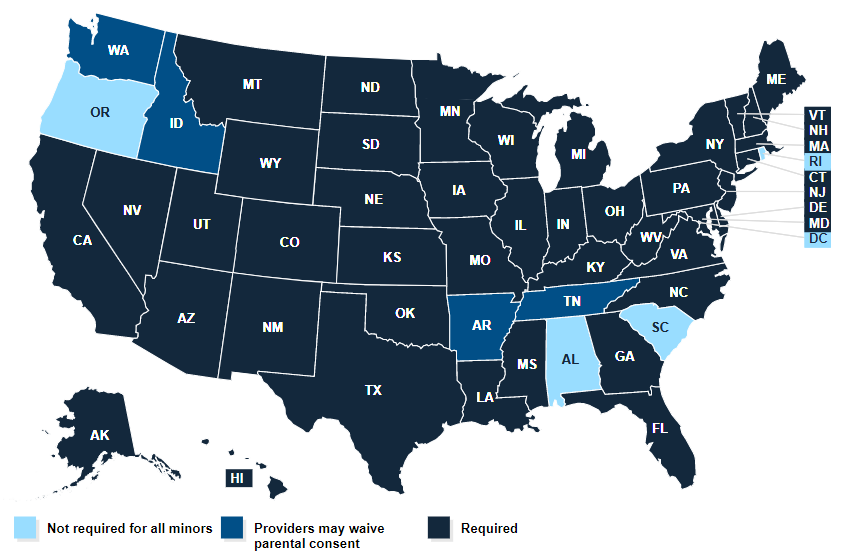

For COVID-19 shots, the majority of the states require parental consent for minors. The exceptions are Arkansas, Washington, D.C., Idaho, Oregon, Rhode Island, South Carolina, Tennessee and Washington.

Also, some state legislators have introduced bills specifically addressing the COVID-19 vaccine for minors. In early November, Alabama enacted a law banning minors from receiving the COVID-19 vaccine without their parents’ consent and banning educational institutions from inquiring about kids’ vaccination status without parental consent. For routine childhood vaccination, the state allows minors who are 14 years or older to get their immunizations without parental consent. North Carolina also passed a law in August requiring parents’ consent for giving the COVID-19 shot to minors, even though the state doesn’t require parental consent for routine childhood immunizations for minors of any age. (In the U.S. a minor is generally defined as a person under the age of 18.)

As of mid-November, 11.5% of 5-to-11-year-old children in the U.S. had received their first dose of the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 shot, two weeks after the vaccine received emergency use authorization for the age group, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention data. Among 12-to-17-year-olds, 51% had been fully vaccinated with the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine, which received an emergency use authorization for this age group in May. Among adults 18 years and older, 71% have been fully vaccinated.

Public health leaders urge vaccination for children to reduce not only the risk of infection but also transmission. Even though the majority of children don’t develop severe disease from a COVID-19 infection, they are more likely to be asymptomatic than adults, increasing the risk of spreading the virus to adults around them.

Between Nov. 11 and Nov. 18, children made up 25% of the reported weekly COVID-19 cases in the U.S., according to the latest weekly Children and COVID-19: State-Level Data Report by the American Academy of Pediatrics. Since the beginning of the pandemic, 636 U.S. children have died due to COVID-19. Worldwide, more than 11,700 children have died from COVID-19, according to UNICEF, a United Nations agency responsible for providing humanitarian and developmental aid to children around the world.

Below, we summarize three recent papers that explore the nuances of parents’ consent laws for immunizations, including COVID-19.

The authors pose two main questions: Should parental consent be required for COVID-19 vaccine administration? And, what if a minor — specifically, 12 years or older — requests COVID-19 vaccination against parental will or without parental knowledge?

The bottom line: There is no definitive, ‘one size fits all’ moral answer, the authors write. “In practice, the process of consent for a minor’s care is somewhat blurry and elusive, again varying by state, type of care, and the specifics of patient health and family circumstances,” they add.

A caveat: Existing consent laws are designed for vaccines that have gone through the traditional FDA approval process rather than the emergency use authorization process, the authors write. “Whether inciting hesitancy and concern — or a motivating sense of urgency and opportunity — the vaccine’s [emergency use authorization] status cannot be ignored, and must factor into discussions about consent policy,” they add.

What else the authors say: With policymakers and medical providers in mind, the authors offer a list of key considerations for vaccinating adolescents against their parents’ consent, including the child’s age, the benefits and risks of the vaccine, the parents’ and children’s concerns and motivations for getting vaccinated, where they are receiving their information from and several other ethical considerations.

The authors’ main points: In this editorial, the authors recommend parental consent policies that grant more autonomy to minors as they get older, while considering the risks and benefits of vaccination.

A brief background on age and medical decision-making: Minors are generally thought to lack the maturity and cognitive capacity to make rational health care decisions before age 14, the authors write. But by age 14, “their reasoning begins to track adult decision-making, weighing in favor of respect for minors’ autonomy to make health care decisions that advance their health, particularly when these choices have a positive effect on public health,” they explain. “In the context of vaccination, some older minors may possess a more accurate understanding of the risks and benefits of a vaccine than their hesitant guardians.”

What’s driving the authors’ recommendations: They express concerns about declining rates of routine childhood vaccinations during the pandemic while anti-vaccination attitudes continue to grow. “In an ongoing public health crisis, children and adolescents should not be placed at continued risk due to their parents’ hesitancy over COVID-19 vaccines,” they write.

The authors’ bottom line: “Children and adolescents have the capacity to understand and reason about low-risk and high-benefit health care interventions. State laws should therefore authorize minors to consent to COVID-19 vaccination without parental permission,” they write.

Study objective: The authors set out to explore the association between vaccination rates and state policies that allow teens to get the HPV vaccine without parental consent.

How they did it: The team analyzed responses to the National Immunization Survey-Teen, which compiles vaccination data for U.S. adolescents. They included data from 2015 to 2018, representing 81,899 adolescents aged 13 to 17 years.

What they found: Adolescents who lived in states that didn’t require parental consent for the HPV vaccine were significantly more likely to get the immunization compared with those who lived in states that require parental consent. Teens who didn’t need parental consent were 33% more likely to get the first dose of the HPV vaccine and 26% more likely to complete the two-dose series compared with teens who needed parental consent.

Background: Three vaccines are routinely recommended for the adolescents: The Tdap vaccine to prevent whooping cough (pertussis), meningococcal vaccine, and the two-dose HPV vaccine. Immunization rates for the HPV vaccine continue to improve since the first vaccine was introduced in 2006. So far, 54% of U.S. adolescents had received both doses of the vaccine, according to the latest available data from the CDC. Meanwhile, most states require parental consent for the HPV vaccine for adolescents. Only Alabama, Alaska, California, Delaware, Idaho, New York, Oregon, and South Carolina, plus Washington, D.C. allow adolescents to get the HPV vaccine without parental consent.

The authors’ bottom line: “This suggests that policies that permit adolescents to consent to HPV vaccination could be an important strategy toward improving vaccine initiation among young adolescents, when the vaccine is likely to be most effective,” they write.

Take note: The study shows an association between vaccination rates and states policies, not causation.

Conflicts of interest: Two study authors have served as a consultant or received personal fees as a scientific advisor to Merck, the maker of the HPV vaccine Gardasil.

Naseem Miller is the senior editor for health at The Journalist’s Resource. She joined JR in 2021 after working as a health reporter in local newspapers and national medical trade publications for two decades. Immediately before joining JR, she was a senior health reporter at the Orlando Sentinel, where she was part of the team that was named a 2016 Pulitzer Prize finalist for its coverage of the Pulse nightclub mass shooting.