There is perhaps no quote more memorable – nor more contentious – from the battle over the Affordable Care Act (aka Obamacare). During the debate, reform critics warned that the ailing Medicare system would be further weakened by government efforts to restructure it. Reform supporters countered that although the program was critical to millions of Medicare-eligible Americans, it could not continue without dramatic restructuring.

In the end, the Affordable Care Act prevailed, and the federal government quickly prepared to unroll a raft of changes and improvements to Medicare. A federal summary of the changes reveals a long list of reforms intended to contain Medicare costs while increasing revenue, improving and streamlining its delivery systems, and even increasing services to the program.

The ACA gradually reduced costs by restructuring payments to Medicare Advantage, based on the fact that the government was spending more money per enrollee for Medicare Advantage than for Original Medicare. But implementing the cuts has been a bit of an uphill battle.

In 2011, the law froze the benchmark amount at 2010 levels for the maximum amount paid for MA plans in each county. Then, in 2012, the government began phasing in payment reductions to Medicare Advantage in an effort to bring Medicare Advantage spending in line with the fee-for-service program (Original Medicare), although benchmark amounts could also increase based on plan quality.

For 2021, Medicare Advantage plans saw an increase in their reimbursement rates, as was the case in 2020, 2019, 2018, and 2017. And these increases came on the heels of similar increases in 2014, 2015, and 2016 – despite the fact that in all three years, payment cuts had been proposed and then essentially reversed or off-set with payment increases.

However, insurers said that their average payment amounts decreased by about 6% in 2014, and by about 3 or 4% in 2015 – clearly, not everyone agrees on the impact of the budgetary changes from one year to the next. And for 2020, the amount that Medicare Advantage plans received was based more on patient “encounter data,” which is a rule change that insurers did not want.

When the ACA was enacted, there were expectations that Medicare Advantage enrollment would drop because the payment cuts would trigger benefit reductions and premium increases that would drive enrollees away from Medicare Advantage plans. In 2011, then-U.S. Representative and Chairman of the House Budget Committee, Paul Ryan, derided the cuts to Medicare Advantage by citing CBO and CMS projections that Medicare Advantage enrollment would be as low as 7.4 million by 2017 – a 50% reduction over the level that they would have otherwise anticipated without the ACA’s cuts.

However, those concerns have turned out to be unfounded. In 2021, there were 26 million Medicare Advantage enrollees, and enrollment in Advantage plans had been steadily growing since 2004.; Medicare Advantage now accounts for 42% of all Medicare beneficiaries. That’s up from 24% in 2010, which is the year the ACA was enacted (overall Medicare enrollment has been growing sharply as the Baby Boomer population ages into Medicare, but Medicare Advantage enrollment is growing at an even faster pace).

Although the payment reform has forced Medicare Advantage plans to be more efficient, utilize smaller networks, and offer more plans with higher out-of-pocket costs, the popularity of the program has grown significantly in the years since the ACA was signed into law, and most seniors have access to at least one zero-premium Medicare Advantage plan. Starting in 2020, CMS began allowing Medicare Advantage plans to have more flexibility in terms of providing extra benefits in an effort to keep patients as healthy as possible; this Kaiser Family Foundation analysis gives an overview of how prevalent the various types of extra benefits are for plans that are being offered for 2021.

Medicare Advantage takes the place of Medicare A and B. For most seniors, Medicare A is free, but Medicare B has a premium of $148.50/month for most beneficiaries in 2021; it’s important to understand that Medicare Advantage enrollees have to pay their Medicare Part B premium in addition to whatever premium they owe for the Medicare Advantage plan, so a zero-premium plan would mean that the person just has to pay the Part B premium.

In 2012, the government also began rewarding Medicare Advantage plans with higher quality ratings. A 5% bonus is paid to plans with a rating of 4, 4.5, or 5 stars. In 2014, plans with 3 and 3.5 star ratings were eligible for the bonus as well, but that’s no longer the case. For 2021, there are 21 Medicare Advantage and/or Part D plans with five stars. CMS noted that more than three-quarters of all Medicare beneficiaries enrolled in Medicare Advantage plans with integrated Part D prescription coverage would be in plans with at least four stars as of 2021.

Starting in 2014, Medicare Advantage plans were required to maintain a medical loss ratio – the percent of premiums that actually goes back to care of customers – of 85%. This is the same medical loss ratio that was imposed on the private large group health insurance market starting in 2011, and most Medicare Advantage plans were already conforming to this requirement; in 2011, the average medical loss ratio for Medicare Advantage plans was 86.3%. The medical loss ratio rules remain in effect, but starting in 2019, the federal government has reduced the reporting burden for Medicare Advantage insurers.

One of the most feared financial drains on enrollees is Medicare’s prescription drug “donut hole.” The issue was addressed immediately by the ACA, which began phasing in coverage adjustments to ensure that enrollees pay only 25% of “donut hole” expenses by 2020, compared to 100% in 2010 and before.

Within months of the bill signing, Medicare began sending $250 rebate checks to anyone caught in the “donut hole.” Then, starting in 2011, seniors began to get a break on the cost of drugs while in the donut hole. In 2011, Medicare D enrollees were only responsible for 50% of the cost of brand-name drugs in the donut hole.

That was scheduled to drop to 25% by 2020, but the donut hole closed a year early for brand-name drugs, with enrollees’ out-of-pocket costs in 2019 capped at 25% of the cost of the drugs (after the deductible was met). It would have been 30%, but that was adjusted to 25% under the terms of the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018.

Since 2020, Part D enrollees have been paying no more than 25% of the cost of both generic and brand name drugs after meeting the initial coverage threshold and before reaching the catastrophic coverage level. Technically, this means that there is no longer a donut hole, but it’s important to understand that the donut hole concept is still relevant: It plays a role in determining how your out-of-pocket costs are counted and who actually pays for your drugs (you, your health plan, the drug manufacturer, or the Medicare program).

When Medicare Part D was created in 2003, part of the legislation specifically forbid the government from negotiating drug prices with manufacturers, and that has continued to be the case. There has been considerable debate about changing this rule, but it has met with continued pushback from the pharmaceutical lobby.

Democratic lawmakers have pushed to allow Medicare to negotiate with pharmaceutical companies, and some sort of negotiating power is incorporated into most of the post-ACA health care reform proposals that have been debated in recent years (ie, various versions of single-payer or public option proposals).

In 2021, most Medicare Part B enrollees pay $148.50/month in premiums. But beneficiaries with higher incomes pay additional amounts – up to $504.90 for those with the highest incomes (individuals with income above $500,000, and couples above $750,000). Medicare D premiums are also higher for enrollees with higher incomes.

The income brackets changed in 2018 so that the highest income bracket (to which the highest premiums apply) started at a lower income level than it did in 2017 and earlier years. Beginning in 2020, the income levels were adjusted upward based on inflation (the ACA had frozen inflation-based adjustments since 2011). The high-income brackets now start at $88,001 for a single individual, and $176,001 for a married couple (these thresholds are expected to increase to $91,000 and $182,000 in 2022).

Some enrollees with income above those limits might have found themselves bumped into a higher bracket starting in 2018, which could have resulted in a significant increase in their premiums. The Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018 created a new bracket, separating what was previously the highest income bracket into two brackets. The highest bracket — which corresponds to the biggest Part B and Part D premiums — now applies to those with income above $500,000 ($750,000 for a married couple) as of 2020. (Married couples filing separately pay the highest premiums if the individual has an income of $412,000 or more.)

But it’s important to note that the high-income premiums only apply to a small percentage of enrollees. In 2013, only 4% of Part D enrollees, and 5% of Part B enrollees, paid additional premiums based on their income; most seniors tend to have low or moderate incomes, rather than high incomes. Thirty percent of Part D enrollees have income low enough to receive additional subsidies to help cover the cost of their premiums.

Click on a state on this map to learn more about the programs that are available to help Medicare beneficiaries who have limited income and assets.

There’s good news for those who believe in an “ounce of prevention.” Since 2011, Medicare beneficiaries have had access to free preventive care, with a free “Welcome to Medicare” visit, free annual wellness visits, personalized prevention plans, and some screenings, including mammograms – all thanks to the ACA.

The ACA also changed the tax code as a way to increase revenue for the Medicare program. Starting in 2013, the Medicare payroll tax increased by 0.9% (from 1.45 to 2.35%) for individuals earning more than $200,000 and for married couples with income above $250,000 who file jointly. The extra tax only impacts the wealthiest fraction of the country – less than three% of couples earn $250,000 or more. Repealing this tax was one of the objectives of the various ACA repeal bills that Republican lawmakers pushed in 2017, but none of the repeal bills passed the Senate (the House passed the American Health Care Act in May 2017, but the Senate’s version failed).

When Medicare D was created, it included a provision to provide a subsidy to employers who continued to offer prescription drug coverage to their retirees, as long as the drug covered was at least as good as Medicare D. The subsidy amounts to 28% of what the employer spends on retiree drug costs. But although that meant that eligible employers were effectively only paying 72% of their total drug costs, they were still able to deduct 100% of those costs.

A general rule of thumb with tax law is that deductions cannot be taken for expenses that are reimbursed, and the subsidy plus deduction aspect of the retiree drug subsidy program wasn’t in line with that concept. Starting in 2013, the ACA eliminated the tax deduction for the subsidized amount that employers receive under the retiree drug subsidy program. The subsidy is still available, and employers can still deduct the amount that they actually pay after accounting for the subsidy (i.e., 72% of the costs, not 100%).

The Medicare Modernization Act of 2003 included a provision to pay 10% bonuses to Medicare physicians who work in health professional shortage areas (HPSAs). The ACA expanded this program to include general surgeons, from 2011 to the end of 2015. After that, the bonus applies to physicians who provide primary care and mental health services.

The ACA includes numerous cost-containment provisions that have been implemented over the years since the law was passed. Many of the provisions involve incentives to health care providers, including payment adjustments to facilities based on productivity, quality outcomes, and use of electronic medical records, along with incentives for providers who demonstrate lowered Medicare spending.

In 2014, about 20% of Original Medicare payments were made through a value-oriented system (based on quality and value rather than simply paying providers on a per-procedure basis). HHS set a goal of increasing that to 50% by 2018, and they have also been focusing on value-based payment systems in Medicare Advantage and Part D. In addition, Medicare has formed a Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation, which tests payment methods and delivery systems that lower costs and improve quality in the system. By 2017, value-based payments accounted for more than 38% of Original Medicare payments, and more than 49% of Medicare Advantage payments.

Starting in 2012 (for hospital discharges after October 1, 2012), Medicare began reducing payments to hospitals with high numbers of preventable hospital readmissions. And starting in 2015, hospitals with a high rate of preventable hospital-acquired conditions were also subject to reduced payments under a provision of the ACA. Both of these measures encourage patient safety and quality control in hospitals, along with better utilization of the tax dollars that fund Medicare.

The ACA called for phasing out payments to disproportionate share hospitals (DSH), which treat significant populations of indigent patients. The payments were initially scheduled to phase out starting in 2014 and be eliminated by 2020, although that’s been delayed several times. The cuts are currently scheduled to begin in fiscal year 2024 (the COVID pandemic has resulted in additional delays, after several previous delays). The idea was that the Medicaid expansion provision in the ACA would eliminate much of the uncompensated care that hospitals had been providing. But Medicaid expansion became optional with NFIB v. Sebelius in 2012, and there are still 12 states that have not expanded Medicaid.

The ACA also prevents new physician-owned hospitals from contracting with Medicare, and prohibits current physician-owned hospitals (that work with Medicare) from expanding. This was implemented with the intent of limiting possible conflicts of interest and practices that would put heavier burdens on traditional hospitals, but it has not been without controversy.

Louise Norris is an individual health insurance broker who has been writing about health insurance and health reform since 2006. She has written dozens of opinions and educational pieces about the Affordable Care Act for healthinsurance.org. Her state health exchange updates are regularly cited by media who cover health reform and by other health insurance experts.

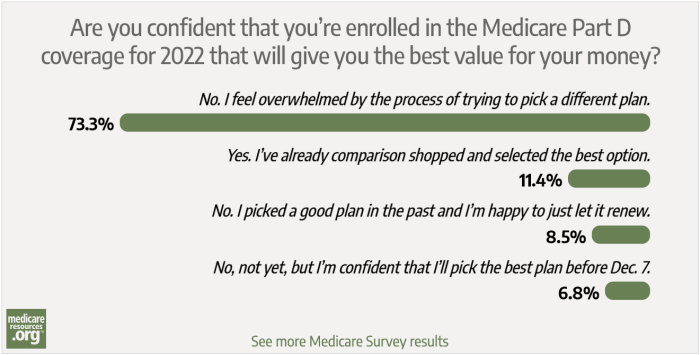

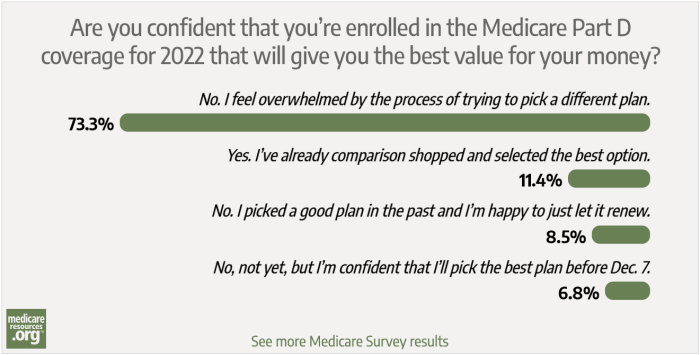

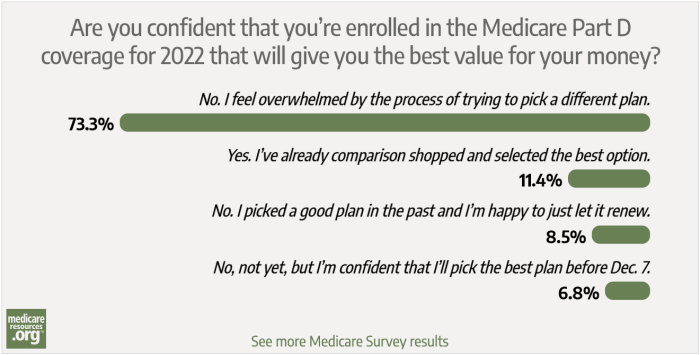

We asked how confident our readers were with comparison shopping for a Medicare Part D plan during the 2022 Medicare Annual Enrollment Period. Here's what we learned from more than 350 survey responses.

Eligibility for Medicare coverage depends on factors that include your work history, health status, and residency status. Check your eligibility today.

Learn how and when to enroll in Original Medicare, Medicare Advantage, Medigap, and Part D coverage. Get plan information and a free quote today.

Enrollment dates for Medicare are critical. Missing an enrollment date could cost you higher premiums down the line — or it could cost you coverage entirely.

We asked how confident our readers were with comparison shopping for a Medicare Part D plan during the 2022 Medicare Annual Enrollment Period. Here's what we learned from more than 350 survey responses.

Eligibility for Medicare coverage depends on factors that include your work history, health status, and residency status. Check your eligibility today.

Learn how and when to enroll in Original Medicare, Medicare Advantage, Medigap, and Part D coverage. Get plan information and a free quote today.

Enrollment dates for Medicare are critical. Missing an enrollment date could cost you higher premiums down the line — or it could cost you coverage entirely.